A look at the evolution of the built environment in the districts of Baia Mare

INTRODUCTION

Enikő Vincze, PRECWORK project manager and WP3 coordinator

- Methodology and structure of the material

Work Package 3 (WP3) of the PRECWORK project contributes to the analysis of the processes of socio-territorial marginalization and systemic marginalization of impoverished Roma as these happen at the intersection between housing, work, and racialization. We understand these processes as effects of the changing regimes of political economy: of housing policies and urban and territorial development, but also, of industrial relations that cause the appearance or disappearance of jobs and resources needed to access housing and pay its costs. All these interconnected factors, together, eventually lead to the peripheralization of racialized social categories and the racialization of precarious housing areas, while other people belonging to the low-income working class do not end up in similar situations.

After a period of documentation through desk research about the past and present of Baia Mare districts, and in order to identify people to interview at a later stage, but, of course, to acquire more knowledge about the city through spatial contact with it, in July and August 2021, the WP3 team made two exploratory visits to Baia Mare. On these occasions, we took several photos of the streets and buildings during long walks through all districts of the city (city walks). Along the way, we tried to discover and understand the evolutions of the built environment in the districts, both through informal discussions with people on the streets (small talks), and through spot documentation from online sources (press, digital publications, websites) or from publications accessible at Baia Mare County Library and archives, steps that we would continue in the near future.

From our photos to finding the systemic meanings inscribed in the built environment (residential, industrial, commercial, office), and in the way in which urban spaces have undergone radical changes over time, we still have a long way to go.

However, we took the courage to make the set of materials presented on the PRECWORK project’s website, as a partial stage result that takes a step above the empirical observations by systematizing the information collected so far, on order to build a serviceable foundation for the immediately following analytical approaches. Members of the WP3 team are George Zamfir, Manuel Mireanu, Andrea Kiss and the undersigned; researchers Cristina Bădiță and Alexandru Burlacu (from WP2), as well as senior researcher Mara Mărginean have also cooperated with this endeavour.

The series of materials intitled “A look upon the evolutions of the built environment in the districts of Baia Mare” has the following structure:

I. Vasile Alecsandri district – the youngest district of blocks of local socialism

II. Depot district – transformations of the Western industrial area

III. Săsar district – the oldest district of blocks of flats, from living in green spaces to the gold mine (with reference to the Red Valley, a neighbourhood of houses/villas and the mine)

IV. Development of the city of Baia Mare through Progresul, Republicii, Traian, and Train Station districts

V. Horea Area and the Phoenix Combine in the Old Town district, or the Eastern industrial area of the city

VI. Incorporation of new peripheries with potential for residential development – Grivița district (North), Borcutului Valley (North-West), Ferneziu, and Firiza (North-East)

2. An overview of the evolutions of the built environment

The free royal town called Civitas Rivuli Dominarum from the 1300s (also referred to as Zazarbánya in Hungarian), in which the Germans had maintained important leadership positions, in the next century, developed as an important mining centre of the Kingdom of Hungary,called Nagybánya or Frauenbach, or Neustadt in the 15th century; the town passed through a medieval urbanization within the limits of the territory called the Old Town today, protected by a solid system of fortifications. The history of the Old Town, and of the Hungarian and/or Austro-Hungarian regimes was not much remembered in the socialist era, even if the latter developed its built environment (including housing) in close connection with the development of mining, similarly to the previous centuries, but at a much slower pace. If, for example, as Fig. 1 below shows, in the approximately 150 years between 1787 and 1941, the economic developments of the city led to a population growth of only approx. 18.000 inhabitants, in the mere 50 years between 1941-1992, the city experienced a population increase of almost 132.000 people.

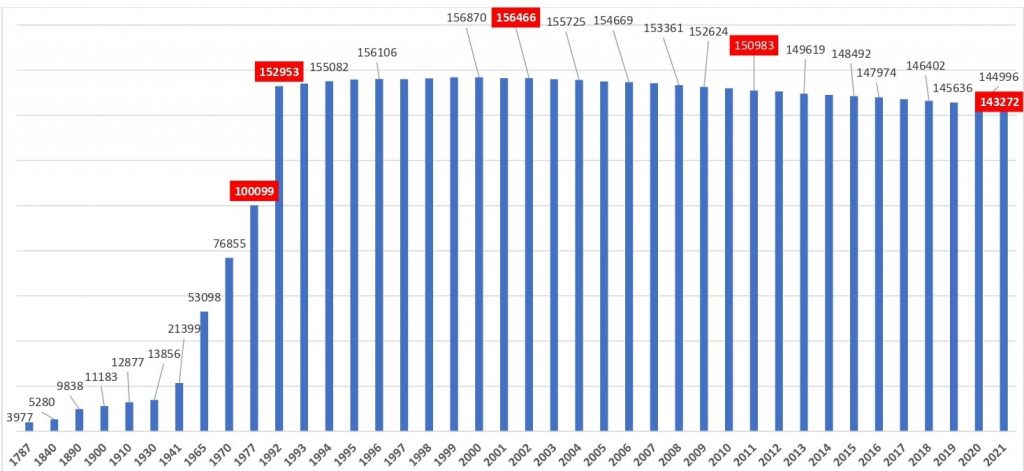

Fig 1. The evolution of the population of Baia Mare

Speaking of the city’s population, the differences in the number of the population identified in the 1992, 2002, and 2011 censuses are to be observed, as well as the number of people living in Baia Mare in the same years seen in the Figure above, that speak about the changes caused by post-socialist deindustrialization. The significant differences between 149.205 and 152.953 (1992), or between 137.921 and 156.466 (2002), or between 123.738 and 150.983 (2011) may include people that left the country during the years of these censuses, but were registered as residing in Baia Mare, or people who had left to other localities in the country due to the loss of jobs, but did not yet change their residence/address on the identity card. Getting back to the aforementioned omission of the Old Town from the official communist narrative: in addition to a multitude of political considerations, this is also due to the fact that, in addition to what had been done during the actual socialism in the East industrial area, incorporated in this district, the housing stock of his municipality developed not in the latter, but by creating new districts in other territories, respectively by expanding the city (including its industrial areas) to the West. A 1975-brochure (“Baia Mare in the age of great accomplishments”) mentions, among others, that in the 1950-1975 period, 400 blocks of flats with 2, 4, or 10 levels were built, which included about 16.000 apartments in the new districts called Progresul, Republicii, Săsar, and Train Station, and plans had already been partially developed about the Decebal district (later, the Traian district), as well as major projects for new block constructions in the South (that was to be the Vasile Alecsandri district).

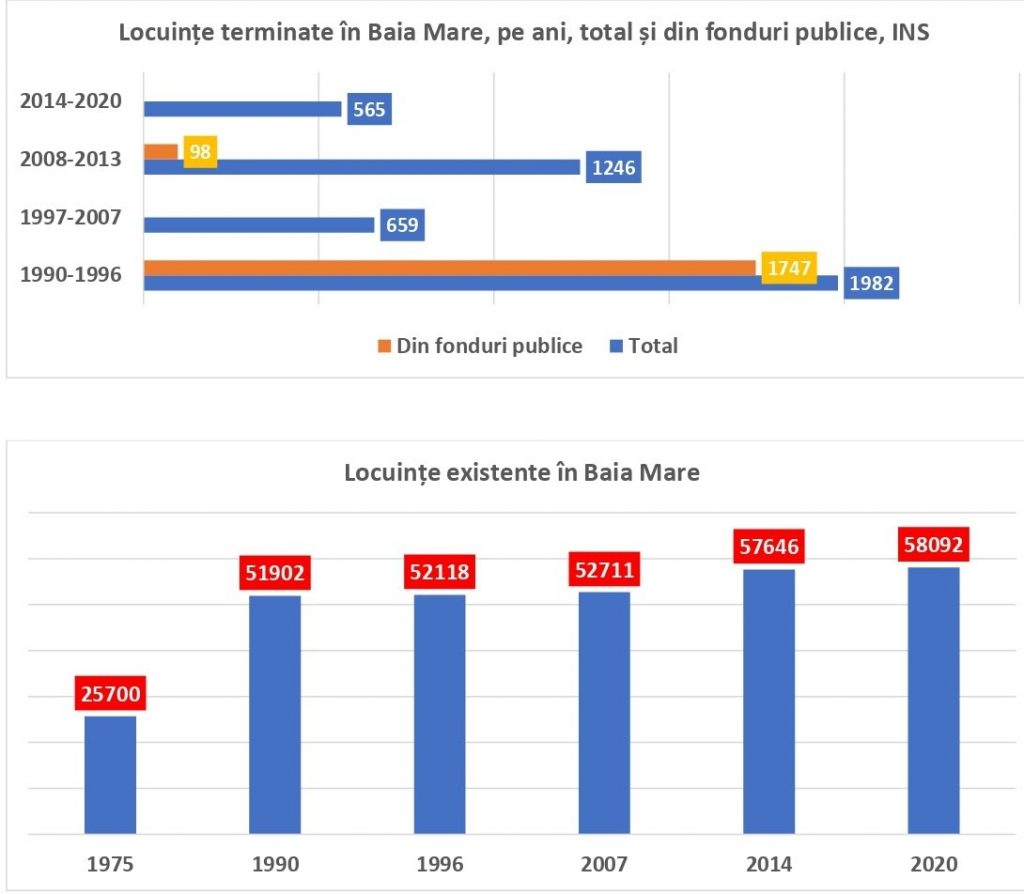

The built asset of the socialist districts mentioned above survived the closure of mining and deindustrialization after 1990, still serving the city’s population: the over 143.000 people with residence in Baia Mare (INS data, Tempo online) live mostly in homes built before 1990. To apprehend this, it is enough to look at the figures in Fig. 2, which show that in the period 1997-2020, only 2470 new homes were built (which is not much, obviously, compared to the 16.000 apartments constructed between 1950-1975, for example); and what was built between 1990-1996, practically meant the finalisation from public funds of the constructions started before 1990 (so that almost 90% of the 1982-houses finished in this period were completed from the state budget). In 1990 alone, almost 1000 homes were finished, which, together with the large number of homes completed between 1990 and 1996, shows that the regime change caught the city of Baia Mare in a full boom of planning the further development of the housing asset. In comparison with the above figures, there clearly are very few new homes that have been completed in the last 7 years (even compared to the period of the 2008-2009 financial crisis and the post-crisis era marked by austerity policies): in total, only 565 dwellings, which include both family houses, and blocks of flats, as follows: in 2014 – 91, in 2015 – 70, in 2016 – 112, in 2017 – 67, in 2018 – 62, in 2019 – 77, and in 2020 – 86.

Fig 2. The evolution of the number of completed and of existing houses in Baia Mare

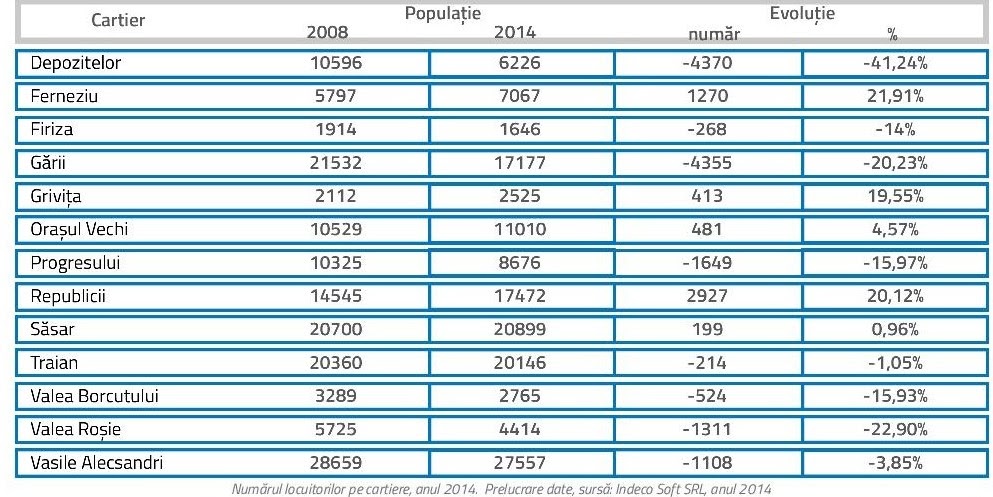

The information presented in the 6 chapters of our material describes some aspects of the history of socialist urbanization, starting from the photos that display the look of certain residential/industrial, commercial, office buildings/spaces in different districts today. But, before zooming on these details, through Fig. 3, let us place the districts on the “map” of the city from the point of view of the evolution of the number of population between 2008 and 2014 (figure taken from the SIDU, 2014 document).

Fig 3. The evolution of the population in the neighborhoods of Baia Mare

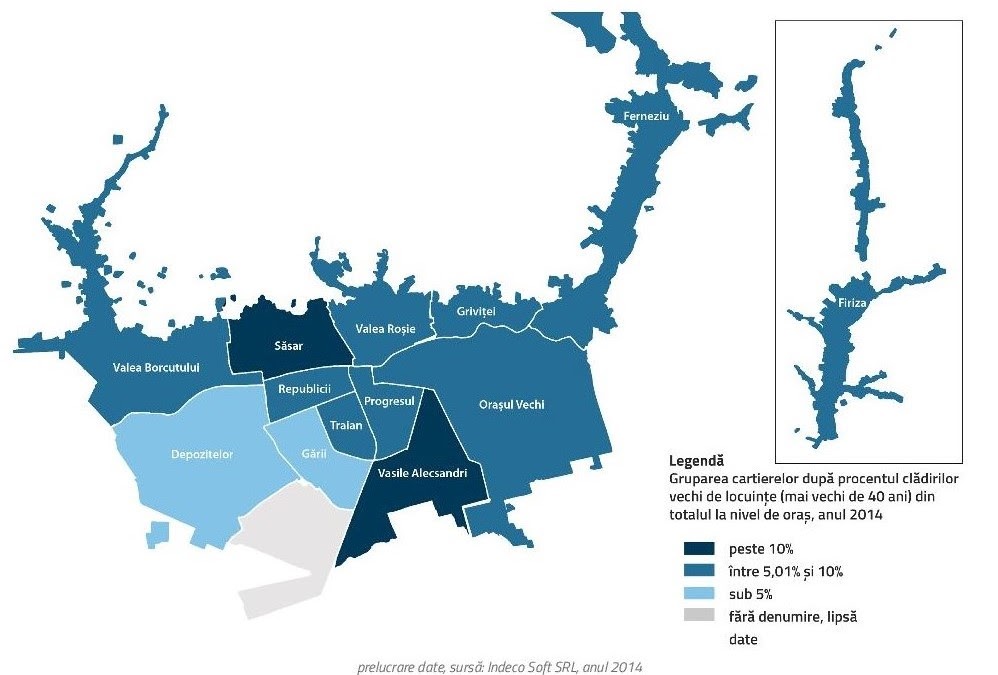

Fig. 4 offers a brief idea about the age of the houses in the different districts of Baia Mare.

Fig 4. Share of old house buildings, 2014

I. “VASILE ALECSANDRI” DISTRICT FROM BAIA MARE

Text created by WP3 in PRECWORK project, through the exploratory field visit in July and August 2021

Researchers: Enikő Vincze și George Zamfir

The former Hatvan district, which all inhabitants of Baia Mare have been calling the “skid row” even before the 1970s, called Vasile Alecsandri today (after the known Romanian poet), is a very heterogeneous neighbourhood in terms of the built environment.

The old blocks of flats and the former non-family workers’ hostels (constructed from the end of 1970 to 1989) are combined with new ensembles made recently by the real estate development company Revolution Residence, but also with new housing blocks from the old state fund renovated by the city hall (called social housing blocks today, from the Melodiei-Rapsodiei area and the Grănicerilor area), as well as with blocks made by the National Housing Agency (some of them finished, like those from Mărăști Alley, and others in construction, on Grănicerilor Street) and with the informal settlement Craica.

The area of “Vasile Alecsandri” also includes small industrial areas (with halls rented out to some transport companies or others) and the territory of the furniture factory, meanwhile demolished, or the remains of Antrepriza de Instalații și Montaj (Installation and assembly enterprise) on Mihai Eminescu Street (named after Romanian national poet).

In his south-east corner the district is very close to the eastern industrial area of the city. To the West, it borders the Train Station and Traian neighbourhoods (which have a long tradition as working class neighbourhoods), as well as the Progresul district (which includes the New Centre of the town), and in East, the Old Town also.

The social status of the inhabitants of “Vasile Alecsandri” district is also very diverse and uneven: from the former workers of various factories and combines that had bought apartments from the state before or after 1990 (some of them already retired), through the impoverished workers living in the informal Craica settlement from the South-East edge of Baia Mare, close to the Eastern industrial platform of the town, to middle class people that can afford to buy an apartment in the new blocks, or to young couples that had the chance to receive a place in an ANL (National Housing Agency) construction, with state-subsidized rent.

II. DEPOT DISTRICT – TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE WESTERN INDUSTRIAL AREA

Material realized by WP3 in PRECWORK project, through the exploratory field visit in July and August 2021

Researchers: Enikő Vincze și George Zamfir

The Depot district is the gateway to Baia Mare from the West (or the Western industrial area), accessible through the County Road 1C, which at one point becomes the București Boulevard, see picture 2). The latter crosses the city on the West–East axis: it enters the city through the new commercial platform (including Auchan, Pepco, Brico, Mercedes, Mazda, and others) and then – through the Depot district, the Republicii, and the Progresul districts –, it reaches the Revoluției Square in the Old Town district, intersecting along the way with main arteries of the South–West axis, such as the Unirii Boulevard, Republicii Boulevard, Gării Street, and several other smaller streets.

North of București Boulevard, in the area up to the Săsar River, next to the above-mentioned store chains, the Depot district includes a Water Treatment Plant and the informal settlement called Pirita in its vicinity. The latter is adjacent to the former pyrite waste dump on the outskirts of Baia Mare (on the border with the one-room apartment blocks on Dragoș Vodă Street, called the “Meda” ensemble), so that the Roma inhabitants of this settlement are affected, in addition to the insecurity and inadequacy of housing, by the toxicity of air and soil, too.

Advancing East through the Depot district, we can cross the area with the address 44 București Bd., which illustrates the real estate developments built on the ruins of socialist industry (picture 3).

This territory includes the new Dedeman (picture 5), Selgros, and Kaufland stores, but also a Diego store (a bit older, opened in 2004), which were built on the ruins of the old and destroyed heritage of the light industry of Baia Mare.

The above-mentioned had appeared in the area after the buildings of Maramureș Textile Enterprise or MARATEX or Maratex Spinning Company (founded in 1972, with about 7000 employees, mostly women, in the 1980s), as well as of FAIMAR Tile and Glass Enterprise (established in 1978/1979, initially with cca. 2000 employees) were almost completely demolished. MARATEX was bought in 2007 by the Red Management real estate investment group, which after not having implemented the real estate project “Radius Baia Mare”, in 2010 sold its assets to the Austrian company Immofinanz through its subsidiary FMZ Baia Mare Imobiliară, which further traded the land to Dedeman (2011), Selgros (2019), Kaufland (2021). An exception to this dominant trend was one of the former administrative buildings of the Maratex company, which today houses, on the same location, a small women’s clothing company called SC STIL AURA SRL (picture 4), established in 1999 with Romanian capital, today with cca. 200 employees, which manufactures exclusively for customers in Germany, Italy, and France. A somewhat similar, however different fate was the one of FAIMAR, which upheld a restricted production line, in a different location in Baia Mare (on 1 Oborului Street); after its privatization, respectively after which in 1992, the decorative and household ceramics section, transformed into the commercial company CERAMAR SA (which operated on 12 Electrolizei Street), seceded from it, in 2007, the joint stock company sold its lands on București Bd. After going into insolvency, in 2021, CERAMAR put its land and buildings up for sale by auction (see pictures 7 and 8).

However, SC FAIMAR SA, after an insolvency procedure was opened for it by creditors in 2018, recovered and it continues its activity today, but only with 120 employees, and in a different location (picture 6). Both SC Stil Aura SRL, and SC Faimar SA operate through outsourcing, with clients from abroad who make and take orders, using cheap local female labour.

As the Western industrial area of Baia Mare, the Depot district is the home, to the south of București Bd., or even on București Bd. (picture 10), of several smaller or larger private companies, functional or bankrupt, in old industrial buildings. For example, on Mărgeanului Street (parallel to București Bd., see picture 9), but also on the adjacent streets that descend further south, among them, on Depozitelor Street, Topazului Street, Bazaltului Street, and Fabricii Street. On the latter, we saw the building where the Stella Artois Brewery was last operating (picture 11), which in 2009 was put up for sale by the GMG IMO Real Estate Agency with the entire land of over 30700 sqm, with all the halls and railway infrastructure.

Also, on Fabricii Street, we found the location of SC Combimar SA (established in 1992 from the former Combined Feed Factory) – see picture 12. The dominant of the entire industrial area is certainly the relatively new ARAMIS Factory (13), with Romanian capital, established by Aramis Invest created in 1994, which became an IKEA partner in 1997. The ARAMIS building is located at the end of Bazaltului Street, the company now has cca. 5,000 employees, many of them Roma, and an assumed CSR program. Further south, on Europa Street (which at one point is actually the bypass road of the municipality), we can find not only the old landfill (picture 14), but also the ITALSOFA Romania production halls. In 2008, the company had about 1,500 employees, being part of the Italian company Natuzzi Group founded in 1959 that produces leather and fabric sofas and armchairs in Romania, China, and Brazil.

Regarding the housing stock of the Depot district, in its eastern part, which is closer to the city, on Motorului Street (in the part south of București Bd.), a few blocks of one-room flats were built (some of them of comfort I, see pictures 15a and 15b), and to the north, four-storey blocks with 2-3 rooms (16a and 16b).

These generally are of lower quality than most blocks in other parts of the city (near new warehouse halls – see picture 17, they have deteriorated even more since 1990, when they had been sold, and the new owners did not have significant funds to maintain them, and on the other hand, the mayor’s office would not make similar investments here besides investments in urban infrastructure in other areas of the city). In the opposite direction inside the Depot district, to the North, at the end of Dragoș Vodă Street, on the outskirts of the city where the former area with pyrite waste (20) stretches, again, we find the aforementioned, less maintained, poor-quality blocks. Google Maps shows them marked as if they formed a distinct district, called “Meda” – see pictures 18 and 19; however, on the official list of districts in Baia Mare, there is no mention of a district with this name, Dragoș Vodă Street being part of the Depot district. All these blocks are in enormous contrast to the nearby so-called Crescent block on 2 Decebal Bd., of 12 levels, built in 1975, placed right in the vicinity of the Depot district, but in the more exclusive Republicii district, beyond the railway (picture 21).

It is important to mention that the distribution of housing to employees in various economic fields, including those working in light industries located in the western industrial area, was not based primarily on the proximity of housing to the workplace. This criterion applied to non-family homes owned by enterprises, but in the case of other types of housing (1/2/3/4-room apartments), the distribution was made on the basis of the quotas that one enterprise or another received from the people’s council in various blocks. Thus, for example, employees of the former Maratex also received housing in the famous so-called Loop Block (see picture 22) on the border between Săsar and Valea Roșie districts, or the intersection between Victoriei and Ciocanului streets (current Iuliu Maniu).

III. SĂSAR DISTRICT – FROM LIVING WITH GREEN SPACES TO GOLD MINE

(including old and new connections with the Red Valley /Valea Roșie/ district and mine)

Material realized by WP3 in PRECWORK project, through the exploratory field visit in July and August 2021

Researchers: Enikő Vincze George Zamfir, Andrea-Erika Kiss; Cristina Bădiță and Alexandru Burlacu

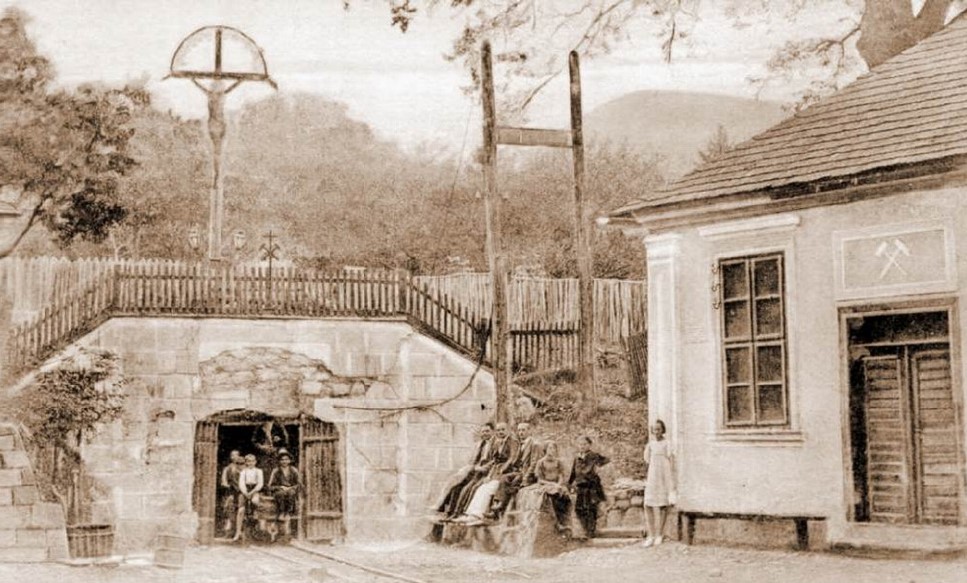

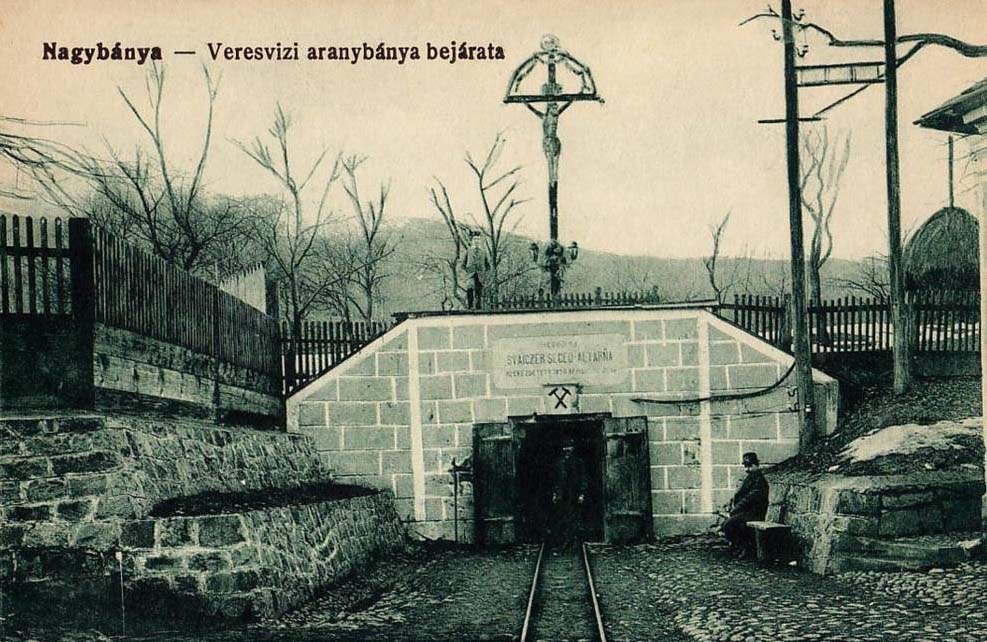

Renowned as a proper model of socialist urban systematization, the Săsar district developed as a diversified territory through the process of expanding to the West of the city of Baia Mare and draining the swamps. Săsar district’s eastern neighbour is Red Valley district, an old quarter of houses that includes both the famous Painters’ Colony that preserves the memory of liberal artistic initiatives from the transition between the 19th and 20th centuries, when cca, 78% of the population of Baia Mare spoke Hungarian as their native tongue, but also, the continuity of the idea of Baia Mare as a city of painters over regimes; as well as the Youth Field, which in 1910, housed an ice rink, then was readjusted in the 1970s by attempts to drain the swampy terrain; and more recently, in 2018, after being rehabilitated in 2015, it gave rise to the Declaration of the Youth of Baia Mare to support the city’s candidacy for the title of European Youth Capital; as well as, last but not least, the entrance to the Red Valley gold mine in the northern part of the former Ciocanului, now Iuliu Maniu Street, also closed down like the rest of the Baia Mare mines at the beginning of 2007 (see images II/37a and II/37b). In fact, the two districts are very different, and not only due to different types of housing (blocks versus houses), but also in terms of population: even if Red Valley has 38 streets compared to Săsar’s 26, the number of people living there in 2014 was five times smaller (4414) than in Săsar (20899). But neither of the two districts has territories defined as marginalized urban areas characterized by very poor housing and ghettoization processes (such as the Old Town, the Alecsandri, the Train Station, or the Borcutului Valley districts). It might be interesting that the same developer (Revolution Residence) is building a set of 3-storey blocks of flats on 83 Victoriei Street (this part of the street belonging to the Săsar district) and another ensemble on 13 Victoriei Street (belonging to the Red Valley district). The connections between the two districts through the two historical gold mines (22 Nucului Street – entrance to Săsar mine and Tudor Vladimirescu Street – entrance to Red Valley mine), as well as through the two recent real estate developments on 83 and 13 Victoriei Street can be seen on Fig. II/38.

As for Săsar district, we would like to first note that in the past, it was planned for the district to have considerable green spaces between the blocks of flats; new traffic arteries through which it connects to the rest of the city (such as Independenței Boulevard); kindergartens, schools (including a high school, with changing functions over the years, construction dating from the late 1960s), even a building built in 1961 for the Pedagogical Institute (whose destinations have changed to this day); medical dispensaries, but also a hospital built in the mid-1960s: the Phthisiology Hospital (called TB at the time); leisure, cinema, or gym locations; district shopping centres such as the Albina complex built in the early 1970s or the RFN complex created in 1985 on a former square; the solid bridge over the Săsar River (the Republicii Bridge, which replaced the old cable bridge in the early 1980s). This diversity has become even more pronounced today; the residential built environment of the district spreads over 26 streets including: a few old houses, reminiscent of the pre-1950s existence of the so-called “ten houses” area; solid two-storey collective housing buildings from the 1950s (constructed, as according to a tenant, by the Soviets for miners); the elegant four-storey brick blocks (initiated on Caragiale Street and extended, in the 1960s, on Cantemir, Porumbescu, Odobescu, Iza streets, all of which continued in the 1970s); the outstanding tower buildings of the 1970s and 80s (10-storey blocks of flats built on Victor Babeș Street, and the 12-storey Loop Block on Victoriei Street, which housed employees from all industries of the city and, being located on the eastern border of the Săsar district, along with Ciocanului or Iuliu Maniu streets, it separated the district from the Red Valley house district); comfort I one-room flats constructed in the mid-1970s (e.g. on George Enescu Street); prefabricated non-family homes on Ghioceilor Street (which housed young workers, with rooms where several people lived together and common bathrooms in the hall of each floor); the new residential complex of houses built by the developer Revolution Residence in 2019-2020 by including a territory from the West of the city in the built-up area; new villas built near the forest and former orchards on Grigore Ureche Street and Sănătății Street; a few blocks recently developed by other private companies, the newest ensemble being the Aleea Noua Residence (summoned by, perhaps, the proximity of the Golden Plaza mall, now taken over by Vivo: it was built in 2010 on the space obtained from the demolition of the former dairy factory, built in 1966); development plans set down in a Zonal Urban Plan, voted by the local council at the end of 2020 that allows the construction of new blocks of 5-6 floors among the old, loosely set blocks.

All these spatial evolutions reflect not only the urbanistic policies of the various regimes and the very different policies of linking work with housing, but also, social inequalities even within the working class before 1990, not to mention the status inequalities after the 2000s among old workers, on the one hand, and employees of new economic fields belonging to the middle class, or the even richer, on the other.

As part of a mining town, the memory of the industry developed around the Săsar gold mine still remains in the district, materialized in several landmarks that can be seen even today, such as: the entrance to the Săsar mine; the remains of the Săsar Flotation (put into operation in 1968, a functional preparation area before the transition to direct cyanide process technology in 1999); the administrative buildings of the Remin company (the National Company for Precious and Non-Ferrous Metals, which went into insolvency in 2009); the (now abandoned) buildings of the mining school or canteen, but also of the non-family homes (some of which have been renovated and restructured, and others in a neglected state, even if inhabited); as well as the ruins of Aurul S.A. transformed into SC Transgold SA and then, into E.M. AURUM (also sold as scrap in 2006, after being held responsible for cyanide leaking from the company’s dam lake in 2000).

IV. DEVELOPMENT OF THE CITY OF BAIA MARE THROUGH PROGRESUL, REPUBLICII, TRAIAN, AND TRAIN STATION DISTRICTS

Material realized by WP3 in PRECWORK project, through the exploratory field visit in July and August 2021

Researchers: Enikő Vincze, Manuel Mireanu, George Zamfir, Andrea-Erika Kiss

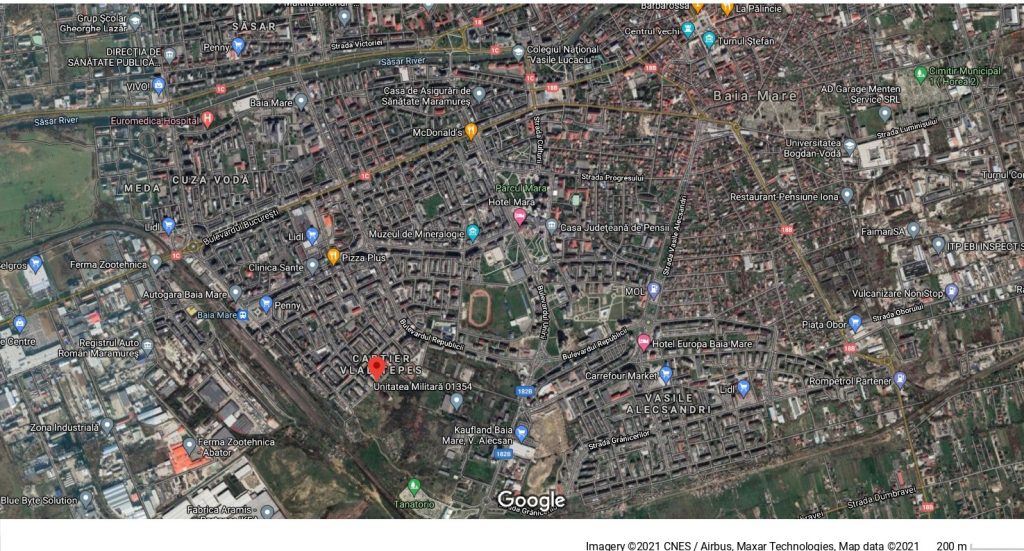

The information and photographs in the following chapter describe, through, but not only, a few examples of buildings, the majority of the residential spaces, four of the city’s districts developed during the period of real socialism. But, before moving on to these details, through Figure 1, let us remember how the Progresul, Republicii, Traian, and Gării districts are placed on the “map” of the city in terms of the evolution of the population between 2008 and 2014 (source of the figure: the SIDU document, 2014).

Figure 1. Evolution of the population in the districts of Baia Mare,

IV.1. Progresul district

Today, the district expands over 19 streets, and it is bordered by the Red Valley district on the north (an old neighbourhood of houses that includes both the famous Painters’ Colony and the entrance to the Red Valley gold mine), on the east, by the historic Old Town, and on south, by the Vasile Alecsandri district (which, however, developed as a new district only in the late 1970s). The Progresul district also includes what was planned to be the New Centre of the city (see figures 10 and 17) with commercial, cultural, and sports or hotel administrative buildings of the socialist urbanization. Some of these are in use at the moment, others are closed down and out of use (for example the Youth House). More recently, the district attracted the headquarters of new banks, IT companies, and the most prosperous real estate developer in Baia Mare. Revolution Residence has 32 projects in Baia Mare, 3 in Cluj, and 6 in Bucharest.

The first blocks of flats in the Progresul district were built in the 1950s, those on Barbu Delavrancea Street and Rozelor Street, following the so-called “Soviet style”, with two solid levels, made of brick, with spacious and high rooms. The Polyclinic on Progresului Street also dates from the 1950s. In the district, the construction of blocks was continued between 1975-1990, with a variety of both the building materials and the level of height (most being four-storey blocks, see pictures 2 and 16, or picture 21 of a more neglected block, but also, 10-level tower blocks lined up on Unirii Boulevard developed on the North-South axis of the city, see picture IV.1/9). The Baia Mare Furniture Factory was built on the eastern border of the district in the late 1950s, privatized and bankrupt after 1990, recently demolished, its land giving way to a shopping centre under construction now.

Impossible not to notice that the unfinished ruin of a building on 24 Unirii Boulevard (see pictures 6), is even stranger than an ordinary ruin, because it is actually a building started before 1990, which entered the state of degradation without ever being completed. In its close proximity (even if in the neighbouring district, Traian) is another building in a similar condition. But, while the latter seems to have to do with the Ministry of Internal Affairs, as it is practically attached to the headquarters of the Intelligence Service on 55 Republicii Bld. (see pictures 6), the unfinished building-ruin in the Progresul district seems to have been given in concession or use to the Orthodox Church, which in turn offers spaces on the ground floor of this unfinished block for various church organizations.

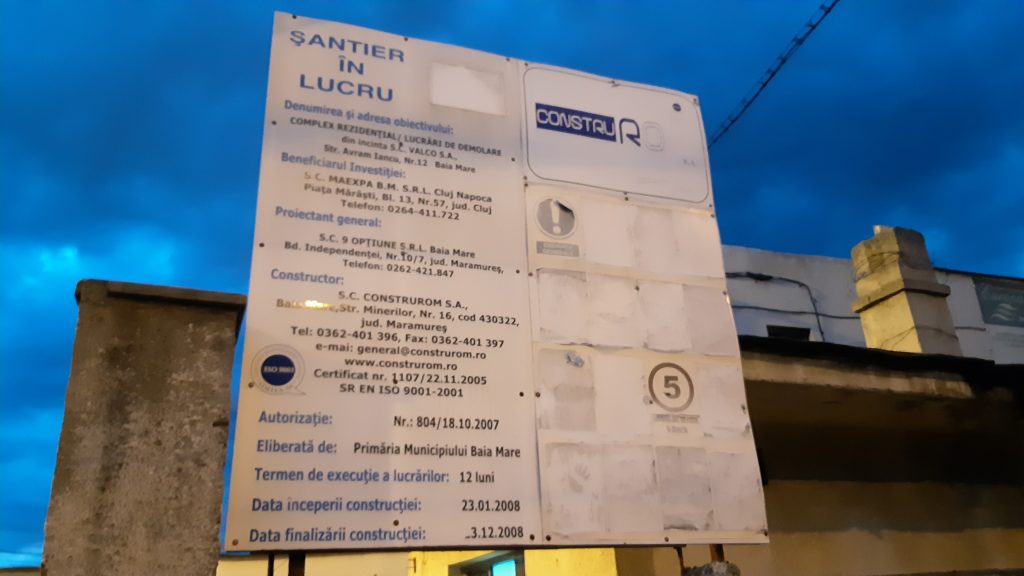

This district has a select residential history; here, we noticed a single private block, now under construction (picture 7), built by a Dutch company through its local partner, but several such initiatives exist in its immediate vicinity on Republicii Bd., officially assigned to Traian district (see pictures 9-11). It should be noted, however, that between 2012-2015, through a DG Regio project, the municipality redesigned the Central Park of the city (picture 19), which increases the quality of life, but also the price of housing in the old and new blocks around it. On a plot of land in the city, on the quiet Serelor Street, through the program of the National Housing Agency, the first ANL blocks in Baia Mare (pictures 15) were built, also from public funds, put into use at the end of 2008. Further away, on the corner of Vasile Alecsandri Street with Unirii Boulevard (picture 18, Europa Residential Complex, investor MAEXPA Cluj and Baia Mare, real estate development launched in 2008 with demolition works in SC VALCO SA, though not completed until today, 12 Avram Iancu Street), close to the Kaufland store and the MAN land on Unirii (IV.1/3), a large shopping centre is under construction on a plot of land where the old furniture factory of the city was demolished (picture IV.1/4). Then, we found an abandoned construction site in the district from 2008, part of a real estate development project left at the stage of demolition of the old building on that land, the works being stopped, maybe for reasons related to the previous financial crisis, but not renewed even in the more prosperous period at national level after 2016.

IV.2. Republicii district

Smaller in size (expanding over only 10 streets, but with two large boulevards among them, București and Decebal), but with more householders than the Progresul district presented above, the Republicii district is less populated than the other neighbouring districts (Săsar, Traian, or Train Station). However, it is one of the few districts in the city that in 2008-2014, experienced an increase in population (see Fig. 1). Back to the history of its built environment, it is worth mentioning that in the late 1950s, the first tower blocks of the city were built in this district, on București Boulevard (picture 1), and at the same time, the blocks with two floors in the former district called Lenin (today Nicolae Iorga Street) were built, George Coșbuc Street was urbanized by blocks of flats built here in the 1960s (picture 6). At the intersection of București and Republicii boulevards, the Maramureș Printing Company has been operating since 1965, named Maramureș Printing House after ‘74, where the newspapers “Pentru Socialism” and “Bányavidéki Fáklya” were printed, among others (picture 7).

In the 1950s, in the western direction, the city kind of ended around Bucharest Boulevard where today, the County Directorate of National Archives (picture 2) can be found and where, nearby (on the corner with Cosmonauţilor Street of the Train Station district) the Enterprise for Processing and Industrialization of Vegetables and Fruits (Agrofruct), once called “Marmalade Factory” was built in the 1970s. In the halls where Agrofruct operated, a commercial complex known as “Center” was settled after 1990 (picture 8).

In the 1970s, the famous Crescent Block was being built for three years in this district, (13 levels) on a land where old houses were demolished, on a street that was later built and developed under the name of Decebal Boulevard.

IV.3. Traian district

This consisting of blocks of flats was designed later than the two districts presented above, in the mid-1970s, with the intention of making it the largest district in the city. The land for the new constructions was set up by the demolition of about 300 old houses. According to the collection of articles from the Glasul Maramureșului newspaper, edited by the former editor-in-chief Dorin Ștef, published in 2014 under the title “Baia Mare de Altădată [Baia Mare of old times]”, the first blocks of flats that were put into use in Traian district were two non-family homes belonging to the former Mechanical Machinery and Mining Equipment Company (IMMUM).

In the era of real socialism, when the designers of the system linked urban systematization with economic production planning, aiming to provide the necessary labour force (which slowly would have settled in the city, after a period of rural commuting), but also complex technological flows on a local level, the local development of the machine building industry was imposed among others to support the continuous development of mining. In addition to IMMUM, in the 1970s, also in this economic sector, the Mining and Repair Equipment Plant (UUMR) was founded, so that, as the statistics from the past show (presented in the volume “Baia Mare la vîrsta marilor împliniri [Baia Mare at the age of great accomplishments]”), out of the structure of Baia Mare industrial production, in 1974, the machine building industry covered 8.5% (after the extraction and processing of ores, respectively non-ferrous metallurgy: 52%; food industry: 21.1%; and light industry: 13.2%). In terms of housing, young employees, without families, were housed in non-family homes, owned by businesses. The homes owned by the state were assigned through county and local popular councils in a different way, each enterprise received a share of the apartments of the new blocks of flats, distributing them among their employees, thus ensuring a social mingling.

Traian district expanded especially in the 1980s in parallel with the Vasile Alecsandri district, and, even though it expands over a smaller area than the latter (it includes three times more streets), it is close to it in terms of population (over 20,000, compared to about 28,000 Alecsandri has). According to the official street organization, the Traian district today includes 10 streets, and it is crossed by two large boulevards: Traian and Republicii, the latter officially belonging in the Traian district and not in the district of the same name. The most famous residential construction is the one on Traian Bd., called legendary the Florin Block, which actually contains five interconnected blocks (picture 1). However, the four-storey blocks in this district also have a special architecture (picture 5), or the 10-storey towers blocks on Traian and Republicii boulevards or Transilvaniei Street (picture 7, 12). Further, the administrative or cultural buildings (picture 3) were also important achievements in the past. The district also benefits from the proximity of the Central Park planned by the mayor’s office between 2012-2015 on the territory framed by Republic Boulevard (of the Traian district) and Serelor Street (officially included in the Progresul district). Out of the relatively few under construction or recently completed blocks in Baia Mare, here we found the most in the city (see picture 11). In this district, we also noticed an unfinished building from before 1990, which is degrading daily like an unfinished ruin, adding to the rest of the socialist residential heritage not yet used. Even if it can be found in another district, physically, this similar ruin building is very close to a similar one on Unirii Bd., mentioned in the description of the Progresul district.

IV.4. Train Station district

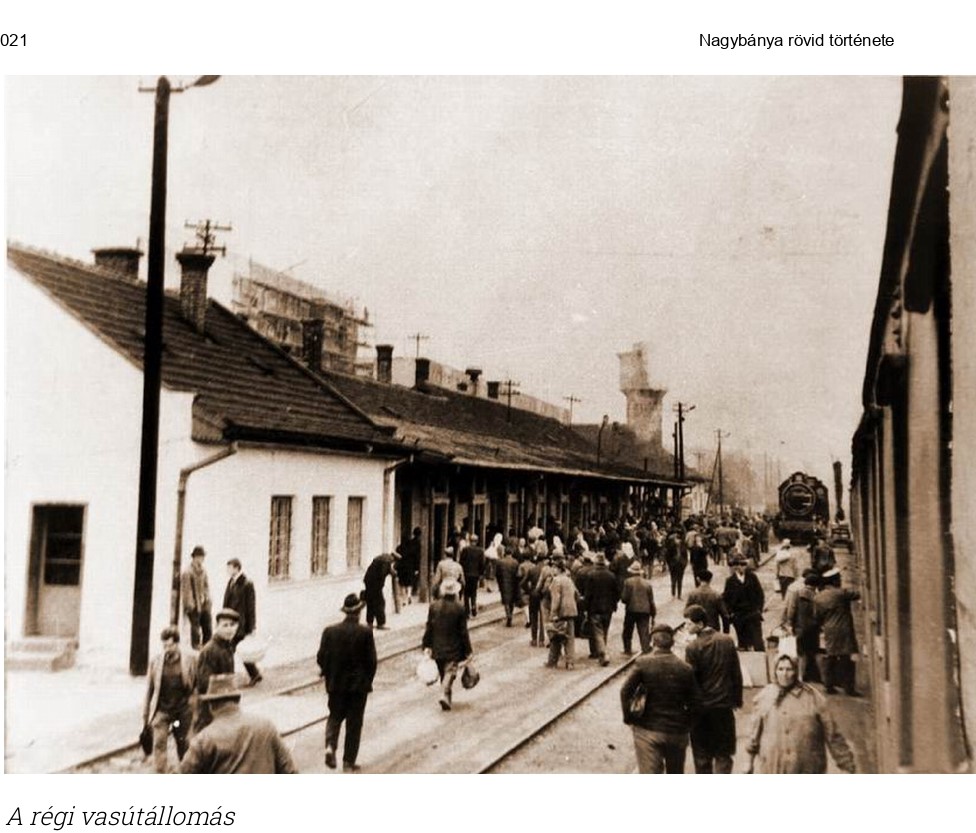

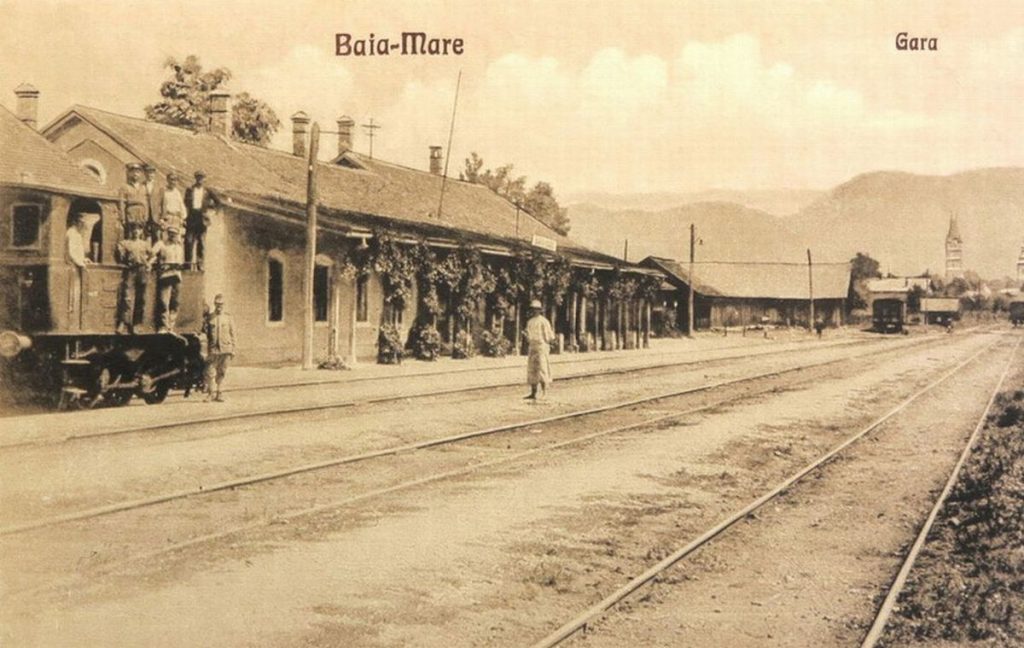

The city’s old train station (see pictures IV.4/1-2), respectively the first railway lines (Baia Mare – Satu Mare, Baia Mare – Dej), including the industrial railways (Baia Mare/Orașul Vechi – Red Valley, Baia Mare – Ferneziu, Baia Mare – Dealul Crucii) were built in the second part of the 19th century, as an endeavour of the capitalist modernization at local level and in the wider geopolitical context. The old railway station operated until 1968, when the new railway station (IV.4/3), built for two years, started its operation. In 2014, compared to 2008 (when it had over 21,000 inhabitants), the Train Station district’s relatively large population was reduced by 4355 people.

Compared to the other three districts presented above, the Train Station district does not have a boulevard (even if, according to its number of streets, it fits their pattern), this being a common feature with another district, the one to its East (Depot), their border being the railway. The Train Station district is crossed from east to west by Traian Boulevard, which, however, belongs to the district of the same name (see Google Maps screen cap of the roundabout in front of the station, where Traian and Train Station districts intersect, Google cap. 4). Traian Bd. divides the Train Station district into two areas with distinct features: the northern and the southern area.

The main street of the district is called Gării (Train Station) Street, which runs parallel to the railway. This street starts from the square of the same name, where tower blocks can be found with shops on the ground floor (picture 5). In general, it does not differ from other streets in the districts built during the real socialism – there are many four-storey blocks along, a few grocery stores on the ground floor and very few houses among the blocks. As an exception, a house is now under construction among the blocks on this street (picture 6). In the area close to the Train Station Square, more neat blocks can be seen, rehabilitated and with gardens around. However, closer to the water tower, there are a row of garages, the reduced comfort type of block also appears on the street, neglected and not renovated after 1990, without the insulation works that have become a standard of about 20 for years now in the maintenance of the former socialist blocs (picture 7).

In the South, Gării Street ends in a square, which the press quotes as an area with “high criminal potential”. It extends to the southeast, along the railway, being marked by a waste dump area, after which, heading to the railway, there are a series of garages and makeshift dwellings. In the “Atlas of marginalized urban areas”, this area is classified as a “slum with houses”, which in turn communicates with the southwest of Vasile Alecsandri district through dirt roads (Grănicerilor, Păltinișului streets, as well as the informal settlement Craica) – see the Google Maps screen cap 10. The vacant space beyond the makeshift houses in the Train Station district is quite large, and it contains several fenced gardens, which do not seem to be related to the makeshift houses (they are somewhat neater and more made of quality materials). We also came across animal tracks. We found similar situations to those on Gării Street on Constantin Brâncoveanu and Vlad Țepeș streets: combinations of orderly and untended four-storey blocks, these streets practically mark the southern border of the Train Station district. These parts of Baia Mare are sometimes mentioned as a separate district, the Vlad Țepeș district (as the Google Maps 11 screen cap also indicates). In fact, Brâncoveanu Street makes the connection between the mentioned waste dump area and Republicii Boulevard, where Sălăjanca Square is located (picture 12). On Brâncoveanu Street, a new residential complex can also be found, which looks like a ‘gated community’ (picture 13).

On the territory that starts beyond Brâncoveanu Street, of about 10 hectares, the Baia Mare City Hall has a plan to build a district of social housing, which would be composed, apparently, of three “social blocks”, as they are mentioned). They have already found a name for this, Pintea Viteazul (the famous outlaw who joined the fight of II. Ferenc Rákóczi, prince of Transylvania, against the Habsburg empire). Geographically, this location seems to be planned as adjacent to a military unit, as well as to the Pintea Viteazul County Constabulary Inspectorate (Google Maps screen cap, 14). The mayor’s statements from January 2021 regarding the beneficiaries of these blocks are confusing: stating that the project will be carried out through an ROP 2014-2020 axis that supports “physical, economic, and social regeneration of disadvantaged communities in urban and rural areas”, it does not mention, however, the communities of this kind in Baia Mare, but only “young people, specialists in various fields, and people who need civilized housing at a low price”.

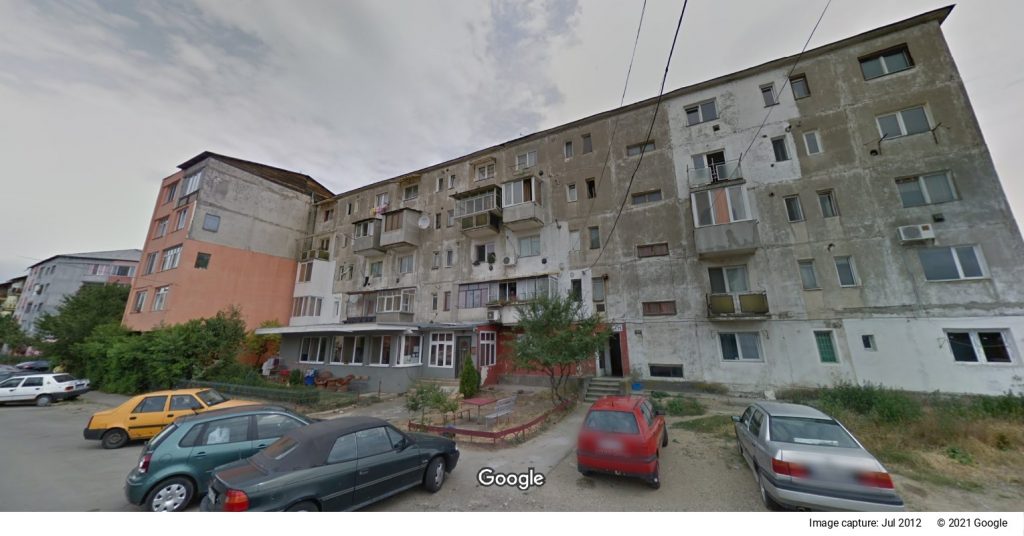

Back to the Gării Square, we met untended blocks in its north, as well as a denser industrial and commercial activity than in the southern part. Located between Traian and București boulevards, this area has streets, such as Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, and Neptun, with blocks without thermal insulation, these are in an advanced state of degradation. Of particular note here is a block on Saturn Street (picture 15). The blocks on Jupiter (picture 16) and Neptune

alleys seem to have been from the past with low comfort apartments, without terraces, and the block on 2 Uranus Street (picture 18) was non-family home, which today is, in turn, used as a block of social housing, that had been renovated by the mayor’s office in 2003 from Swiss funds. The latter are in more or less accentuated contrast with the tower blocks of the district, a contrast that speaks of the inequalities between the categories of the working class during the period of real socialism.

It is also worth mentioning that in the Train Station district, between Saturn and Cosmonauţilor streets, there are the buildings of the former cannery, which were transformed into a more modest local shopping centre (IV.4/19a and IV.4/19b). There is also a market and a Lidl supermarket in the same area (picture 20). To the east of Cosmonauţilor Street, between the shopping centre and Republicii Boulevard, there are several villa-type houses, which function as guesthouses (picture 21). At the same time, in this territory, we noticed a real estate project of collective housing with 3 floors plus attic, by the developer SC Placo Still SRL (picture 22).

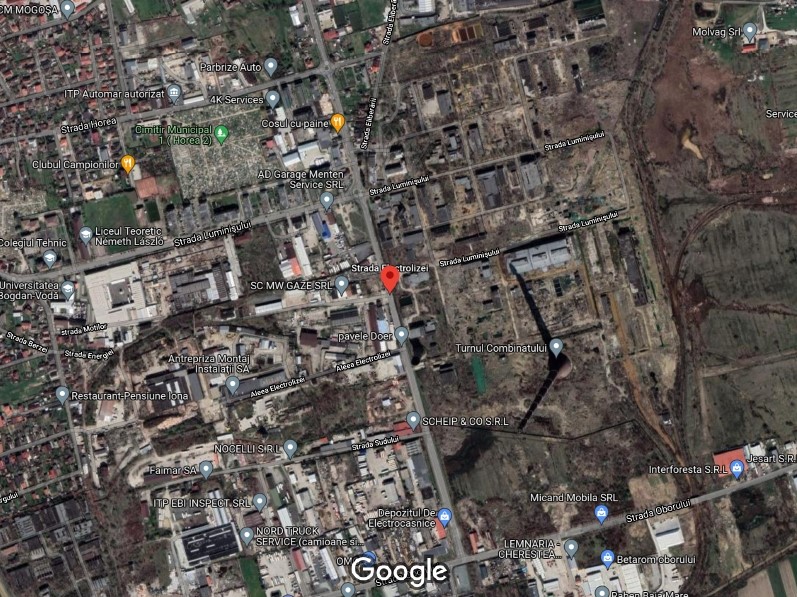

V. Horea Area and the Phoenix Combine in the Old Town district, or the Eastern industrial area of the city: Horea – Electrolizei – Luminişului district

Material realized by WP3 in PRECWORK project, through the exploratory field visit in July, August, and September 2021

Researchers: Manuel Mireanu, Enikő Vincze

According to the geographical borders of the districts of Baia Mare, this area is part of the Old Town. However, this one is entirely different from the urban territory with historical heritage of which both the municipality, and the inhabitants of the city are proud of, trying to capitalize on it as a tourist destination. Here we are, in fact, in the antechamber of the eastern industrial area, where there is a district shaped by the streets Horea to the north, Electrolizei to the east, and Luminişului to the south. This space is a pole of the local degraded built environment, being known not only for the combine of gold, silver, and copper that operated here since the beginning of the 20th century, but also for the wall built by the Cherecheş administration ten years ago. This wall separates two social housing blocks from Horea Street. Even though the mayor’s office called it a “protective fence” (see for example the November 2014 statement)[i], it symbolically contributes significantly to strengthening the spatial and social segregation of Roma living in the two social blocks.

Even though the mayor’s office called it a “protective fence” (see for example the November 2014 statement),[i] it symbolically contributes significantly to strengthening the spatial and social segregation of Roma living in the two social blocks.

Horea St. sets off from the city centre. Up to the social blocks, the street has mostly houses. At no. 28b is a house under renovation. At no. 42, there is a new kindergarten, with a strong secure fence. Before reaching the social blocks, there is a cemetery on the street, which in a way signals the end of the respectable residential area, as well as the beginning of the industrial area and the territory marked by severe housing deprivation. Just before the blocks of flats, there is the office building of the Romanian-German company 4K Services (having two fields of activity: the assembly of electrical components, and the processing of cellular rubber). After the intersection with Electrolizei Street, Horea Street extends in the direction of the former Cuprom industrial platform, having on the left side several houses in whose yards various garbage and huts are collected (photo 1). At the end of the street, where Horea intersects with Eliberării Street, there is a vacant lot (photo 2), as well as industrial spaces (photo 3). The end of Horea Street is, in 2021, the object of an urban development investment plan, which provides for the extension of the street by 1273 meters.[ii]

Back to the three blocks on Horea street no. 46 – these are numbered, from the centre to Electrolizei Street with A, B, and C.

Block “B” used to be the non-family home of the Antrepriză Montaj Instalații company and became the property of the municipality in 2001. Now it is completely renovated. The decision for it to be emptied and to enter under works dates back to 2011, but it was only in June 2017 that it was announced that the time had come for it to be cleared out.[i] Meanwhile, in 2015, the local public administration decided to transfer the social housing fund from Baia Mare under the administration of the Public Social Assistance Service, believing that those who live in “social housing” also require social services. On the occasion of our visit in September 2021, block 46B on Horea Street was still empty, surrounded by a barbed wire fence (photo 4). And about two years ago, in January 2019, Mayor Cătălin Cherecheș declared: “Social housing is not housing for Roma people. Social housing is for the people of Baia Mare! … these are for those who work, care for children and focus on educating children.”[iv]

Concerning block 46A on Horea Street (photos 5 and 6), it used to be a non-family home for the Phoenix plant. Inhabited in the early 2000s by undocumented people, it was purchased from Cuprom SA in 2006, in a state of advanced degradation, first by a businessman, and then by the Baia Mare City Hall. The mayor who made this transaction, Cristian Anghel (who paid a price four times higher than the purchase price the businessman paid to Cuprom a few months ago) was criminally investigated for this very reason. Block 46A was renovated in 2009, and in 2021, at the end of a decision-making process started in 2017, the Baia Mare Local Council decided again to rehabilitate the block.[v] Talking to its residents, the vast majority of them of Roma ethnicity, we found that, beyond the elements that create sources of infection, or the small living spaces in this block, their despair is due to permanent insecurity: “The mayor’s office is still threatening to move us from here, and not only those in debt, but everyone, and we don’t know where they want to move us”; “They tell us that the block’s renovation is about to start, so we will have to get out of here, as was the case of the other block next to us, which is now renovated, but empty, so they threw the tenants out. there and many of them could not return to social housing in the city.”[vi]

Block 46C, located at the corner of Horea Street and Electrolizei Street, is not renovated (photos 7 and 8). The wall stops at the entrance to this block, which is not owned by the city hall (photo 9). Beyond the corner between Horea and Electrolizei streets, opposite the entrance to Cuprom, there are two other even more neglected blocks (1-bedroom flats or apartments with reduced comfort in private property). Together, they form a complex of five blocks whose current state illustrates the precarious financial situation of the tenants (photo 10).[vii]

Along Electrolizei Street, passers-by can see mostly industrial spaces and many dilapidated and / or broken-down buildings. The main economic target on this street is the former Phoenix plant, where tens of thousands of tons of gold, silver, and copper were once produced. Privatized in 1998, the plant was renamed SC Cuprom SA in 2003, after being taken over by new owners, and in 2009, it went into insolvency (photos 11 and 12).

In 2012, a number of 100 families, evacuated from the informal Craica settlement were moved in three empty buildings (one office and two laboratories) of the plant (photo 13). This resulted in many protests, since in their new “homes”, about 20 people were poisoned with chemicals. Moreover, these houses were located in one of the courtyards of the so-called “Death Plant”, once famous for its very high degree of pollution. The evacuation and relocation took place during the first term of Mayor Cherecheș, who at that time was determined to abolish the entire informal Craica settlement (which did not eventually happen, until the moment of writing this text).

with the entrance to the plant

as seen from Electrolizei Street

Even if, despite the immediate proximity of the plant (photo 14), some consider that moving from the Craica barracks to the Cuprom blocks had brought a small improvement in their lives (having access to water and toilets), many today say that they would like to move back to Craica, because the living conditions in Cuprom have deteriorated a lot. [viii]

After the Cuprom buildings inhabited by Roma families, the real industrial area begins, since Electrolizei Street is populated with buildings of the former plant (photo 15), an empty lot, as well as other industrial spaces. The Cuprom gate reads: “Private property S.C. Bitmine SRL” (photo 16),[i] and on the wall around the area of the former factory, there are drawings similar to those on the wall of Horea Street (photo 17).

Cuprom industrial platform

At the corner between Electrolizei and Luminişului streets (photo 18), there is a renovated L-shaped social block, with the address of 13 and 13A Luminișului (photo 19 and 20). According to the discussion with a Romanian female tenant from here, we found out that this social block also has mainly Roma tenants, but the problem for them is not the cohabitation in that particular block, but the proximity of the buildings of Cuprom, where many social problems have accumulated.[x] The block was renovated in 2009. In 2020, the City Hall and the Local Council of Baia Mare decided that this block would be renovated again. The tenant we spoke to told us that they had not been told where they would be moved for the period of the renovation, nor if they would be able to move back after the work was completed.

with the social housing block

Walking on Luminişului Street towards the city centre (to the west), there is a series of blocks (photo 21). Of these, some seem to be neat, even have gardens around (photo 22), while this aspect is absent in the case of the blocks on Horea and Electrolizei streets. Other blocks on this street have shops on the ground floor (photo 23).

with the social housing block

However, the last blocks on the street, from the west, are also precarious and neglected (photo 24). Opposite them, there is an industrial area with the ruins of an old factory (photo 25). At the end of the street, close to the city centre, there is a high school (photo 26), and across the street, the office building of Sifa International (photo 27) can be found, a shoe manufacturer, with production buildings elsewhere, but also in the eastern industrial area of the city, on Universității Street. The neighbourhood formed by the three streets described above, formed in the vicinity of a failed and devastated industrial platform, famous for the times when it functioned due to the production of gold, silver, and copper, as well as its high degree of pollution, is presented today as an area of exacerbated marginality and material deprivations accumulated over the decades. Coming from the city centre, this marginality is visible starting with the two social blocks surrounded by the famous wall on Horea Street, and culminates with the dilapidated and degrading buildings of the former Cuprom plant on Electrolizei Street (photo 28). They show a grim image of severe material deprivation, or of a veritable slum, whose occupants, even if they work for Aramis (the well-known local Roma employer in and around the city) or the Drusal sanitation company, have no resources that would afford them to move to adequate housing in the city. The gloomy landscape of housing deprivation and the memory of the toxic environment is complemented by police cars that frequently patrol the area. Both the authorities, and the citizens consider this area to be “unsafe”, which leads to the constant presence of law enforcement troops on the streets of the area.[xi]

on Luminișului street

Note :

[i] Quote of the statement in a 26 November, 2014 article, see here: https://www.hotnews.ro/stiri-administratie_locala-18671367-video-fotogalerie-primarul-din-baia-mare-pictat-zidul-care-construit-2011-pentru-separa-doua-blocuri-locuite-mare-parte-romi-restul-comunitatii-edilul-spune-transformat-intr-opera-arta-atrage-turisti.htm

[ii] See the Local Council’s resolution here: – https://www.hcl.usr.ro/baiamare/2021/h184

[iii] See the official statement, quoted in a 28 June, 2017 article here: – https://ziarmm.ro/blocul-46b-trebuie-eliberat-locatarii-vor-fi-scosi-din-imobil-blocul-intra-reabilitare-totala-vezi-aici-cine-va-locui-pe-horea-46b-dupa-reabilitare/

[iv] Statements quoted in a 16 January, 2019 article: http://jurnalmm.ro/primarul-municipiului-baia-mare-catalin-chereches-locuintele-sociale-nu-sunt-locuinte-pentru-romi-locuintele-sociale-sunt-pentru-baimareni/)

[v] See the Local Council’s resolution here: https://www.hcl.usr.ro/baiamare/2021/h218

[vi] Interview with the residents of Horea Street, Baia Mare, 10-11 September, 2021.

[vii] Photos from this area, taken in 2011, can be seen in the article accessible here: https://www.dor.ro/dincolo-de-zid-integral-din-dor-7-2/

[viii] As seen in the 2013-BBC film, accessible here: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-25413737

[ix] For more information about the owners of the Cuprom platform, see: https://2mnews.ro/exclusiv-cine-a-cumparat-platforma-industriala-a-combinatului-cuprom-baia-mare-si-ce-interese-planuri-au-noii-proprietari/. About the plans of the administration regarding this area, see: https://www.administratie.ro/un-parc-industrial-si-altul-tehnologic-in-atentia-primariei-baia-mare/

[x] Interview with a resident on Luminişului Street, Baia Mare, 10 September, 2021.

[xi] For similar stories, see: https://www.axanews.ro/old/se-intampla-in-baia-mare-barbat-talharit-in-zona-electrolizei.html

Labor and Migration

Material realized by WP5 in PRECWORK project, through the exploratory field visit in July and August 2021

Researchers: Gabriel Troc, Dana Solonean, Hestia Delibaș

Fieldwork

As planned, fieldwork took place in the cities of of Baia Mare and Sighet, in the villages of Ieud, Bogdan-Vodă and Dragomirești, and in some migrants’ main destination cities in Northern Italy. Gabriel Troc (SR) participated in the orientation trip in Baia Mare in February 2021, and later did extended fieldwork in July and August 2021 in Ieud, Bogdan-Vodă, Dragomirești and Baia Mare, and in August 2022 in Sighet. In September 2022 he did fieldwork in Northern Italy. SR worked mainly with rural migrants (both Romanians and Roma) and collected archival documents from Baia Mare National Archive. Dana Solonean (JR) has collected data in Baia Mare in June 2021, August 2021, and August 2022. She worked mainly with middle-aged Romanian migrants, having worker or middle-class background, who returned after a longer period abroad. She also collected archive data from the Baia Mare National Archive, statistical data from the County Statistical Archive and various literature regarding city development from the Baia Mare municipal library. Hestia Delibaș did fieldwork in July, August and part of September 2021, and again in April 2022, in four Roma communities from Baia Mare (Craica, Pirita, Gării, Ferneziu), where she collected mainly interviews. In total WP5 members spent more than 4 months on the researched area.

During these periods of fieldwork, we collected interviews, oral histories, archival and statistical data. We also contributed to the elaboration of the project’s survey on Baia Mare, on the issues related to migration and labor, and later to the primary analysis of the results.

The selection of the interviewees aimed to cover a wide variety of individual situations, looking after a balanced proportion between men and women, individuals with various labor and migration history (including people over 55 with an employment history during socialism), workers and middle-class individuals, Romanians and Roma, city dwellers and villagers.

The interviews were focused on the past and present mobility of the labor force; the formation of an industrial labor forced out of peasantry during socialism; the education and qualification of the workers; changes in qualifications in the last decades; the impact of deindustrialization in peoples’ lives; strategies of coping with labor deprivation, with a focus on transnational migration; types, frequencies, routes and regimes of migration; remittances level, use and investments; return migration; causes for the persistence of migration in the new context of Baia Mare re-industrialization.

Centralisation of data

The empirical phase has resulted in a corpus of interviews, archival data, statistical data, and press reviews, as following:

Interviews:

*22 interviews with Roma individuals and families (11 men; 14 women, age 25-68), from Baia Mare, belonging to the communities of Craica, Pirita, Gării and Ferneziu;

*4 interviews with Roma families (4 women, 6 men, age 20-64) from Ieud;

*8 interviews with Romanian internal migrants during socialism (from rural to Baia Mare, age 59-82);

*21 interviews with Romanian transnational migrants from Baia Mare (age 23-51, male and female) to UK, Italy, Spain, Germany, Austria, Canada;

* 12 interviews with Romanian internal and transnational migrants from rural area (Ieud, Bogdan-Vodă, Dragomirești) and Sighet, in Italy and France;

*7 interviews with Romanian transnational migrants from Ieud at their present migration location (various localities in Northern Italy);

*4 interviews with local authorities (mayor, school headmaster, elementary teacher, Greek-Catholic priest) from Ieud.

Regarding type, most of the interviews are unstructured and semi-structured interviews; some are life stories or family stories focused on the migration process. 90% of the interviews have been audio recorded.

Archival data:

Three archives/libraries had been consulted (The National Archive of MM County; The County Statistical Archive, and the County Public Library) and various documents have been photocopied, most notably: statistical data regarding population natural and migratory movement (yearly, 1959-1973); demographical data (1981-1990); county labor force synthesis: number of employees, employees housing status (1973, 1975, 1980); labor force resources (1976, 1977, 1978, 1983, 1984, 1985); workers qualification situation (1976, 1978, 1986, 1988); labor force employment (1983, 1984, 1985).

Press Reviews:

We produced two press review databases, one regarding the reflection of the local industry transformations and the other related to transnational migration. The databases comprise of articles available online, from local and national newspapers, starting with 2004, which discuss issues like: factory and mines closing, industry privatization, collective layoffs, new greenfield investments in BM, children with migrant parents, shortage of labor force for local industry, work opportunities abroad, labor condition for the migrants, abuses in labor relations, and more.

Data processing:

Regarding the processing of the collected data, 54 recorded interviews have been transcribed. The interviews were coded and anonymized, and they are under software-run qualitative analysis.

As of this phase of the project, we made – in collaboration with WP1 – a preliminary analysis of the data on migration from the project survey and drew out relevant info regarding labor transnational migration from BM. For example: almost a quarter of the respondents had worked abroad in the last 20 years; Roma migration is as high as the non-Roma; men migrated 2,5 times more than women; few workers with a labor history during socialism (+50) had migrated; the most important migrant category consists of the age group 30-49, namely those who became sociologically adults between deindustrialization and reindustrialization; Roma migration is more precarious than the non-Roma (an average of 1,6 years versus 4,1 years); employment abroad without a contract is still very high (40%); remittances are mostly used for day-to-day subsistence.

The ethnographic research and interviews within the Roma communities from Baia Mare has been analyzed for the April 2021 internal report and produced a first overview of the specific features of Roma migration, such as: a high occurrence of internal and international migration; a high recurrence of migration process; most of the remittances are used for day-to-day consumption, repaying debts and housing improvement in the shanty towns; the Roma transnational status is weak etc.

The resulted text was presented by SR in August at an international conference and published in the conference proceedings (https://www.eucongress.org).

The statistical analysis, mobility and demographic data and county level economic data are exploited in three articles which are in progress. Namely: One article investigates the consequences of transnational migration for the economic development of the researched area, challenging the classical assumption of the relation between various types of remittances and local development (SR); one article investigates how circles of debt, dispossession and underemployment the Roma are facing lock their communities in poverty and underdevelopment (JR2); and one article is focusing on the dynamic of the family in transnational migration and how the gender roles are played and reshuffled in the migration context (JR1).